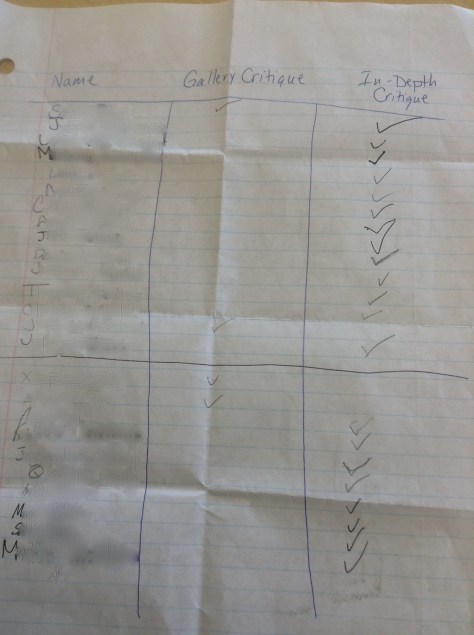

Four students in each of my English classes have had what Ron Berger describes as an “in-depth” critique. I have graded some of those essays, and I can see a great deal of improvement. In some cases, I believe the student’s essay earned a full letter grade higher because of the editing and revision. Obviously, I’m very pleased with these results. Grades are not the most important thing to me. I see improvement in their writing, so naturally a higher grade is the result.

Four students in each of my English classes have had what Ron Berger describes as an “in-depth” critique. I have graded some of those essays, and I can see a great deal of improvement. In some cases, I believe the student’s essay earned a full letter grade higher because of the editing and revision. Obviously, I’m very pleased with these results. Grades are not the most important thing to me. I see improvement in their writing, so naturally a higher grade is the result.

On Monday, we had what Berger calls a “gallery critique” of the remaining essays in each class. Students asked that we simply share Google Docs with view/comment privileges only with everyone in the class. Hapara makes this very easy, as it creates groups for each of your classes. Sharing a document requires that either the student or the teacher click on Share, and then type in the name of the group. We changed the settings to “Comment,” as the default is “Edit.” That’s it.

One of the things I noticed during our gallery critique: Students were reading and reflecting on the comments of their peers in addition to the essays themselves. In fact, some were even replying to the comments of others, which is a great Google Docs feature I think few people know about, much less use. One student called across the room to another, asking her to read his paper because he noticed she had really helpful comments.

A roomful of editors brings out some interesting talents I might otherwise not have known about. For instance, one of my students is really great at making a suggestion that leads the writer to generate ideas. His suggestion might be a subtle nudge. I wrote about one of his suggestions in my second post about Writing Workshop. In that post, I described how one student suggested perhaps Queenie in “A&P” didn’t really “boss” the other two girls around, and it was this other student who suggested perhaps describing the girls would be a good opportunity to bring in the metaphor Updike uses of describing the customers as sheep. Then, the student himself thought he could describe Queenie as herding the girls around the store. Leading a peer toward coming up with the perfect revision on his/her own is truly an outstanding gift.

We have another student who comes up with excellent ways to bring in vocabulary. I assign vocabulary from the literature we read, so the words are in context, but they are also common SAT words. One thing I’ve found frustrating over the years is watching my students study long list of vocabulary words given to them by their SAT tutors. The words are completely out of context, and I would be surprised if students really learn most of them. The other day, one of my students mentioned to me that he had the word “sacrilege,” one of our recent words, on another vocabulary list in World Civilizations (our 9th and 10th grade history course).

Another student uses the commenting feature to talk to himself about his writing. He makes notes about where to bring in textual evidence or where to flesh out details. On a short story assignment he’s working on, I noticed he is making notes about a symbol he wants to incorporate into the ending. If not for Google Docs, I would not be able to see this metacognitive process in action, and it’s fascinating to watch him think.

The culture shift in the classroom was subtle, but palpable. After critiquing a few papers, they all suddenly became a community of writers. There is an openness and camaraderie among them. Writing Workshop days are so much fun for all of us. There is an energy in the room that’s hard to describe.

If you do Writing Workshop in your class, my suggestion is that you start with an in-depth critique rather than a gallery critique. I think students learn how to help their peers when they see it in action. Like anything else, peer editing should be modeled. Another strong suggestion I have is to use Google Docs. Google Docs have made the whole process much easier. I am also seeing students use Google Docs for their other assignments and for taking notes, too.

I came up with the following potential criticisms:

- This takes a lot of time. Yes, it does. We have an open gradebook, so I did fear students and parents would not like the amount of time that elapsed between an assignment and feedback on that assignment. I think the answer is in the results. So far, I am seeing much better and more thoughtful writing from my students. I used our open gradebook to communicate on the assignment about what we were doing, and why there might be a delay in feedback and evaluation as a result.

- Yes, but what can the students do on their own? I would argue that they will learn much more about writing in this way than they would if they did a one-and-done draft, barely glanced at my comments or rubric, and only hunted for the final grade. I have seen much more active revision, even after workshop is over. Students are thinking longer and harder about their writing. When in our adult lives do we have to write anything that we are forbidden to obtain feedback on?

- Won’t this lead to higher grades? What will happen when it comes time to recommend students for Honors/AP? We can’t let all of them in! Cards on the table: I have issues with AP. I think students, parents, and colleges are overly concerned with AP courses. I am not convinced by teachers who describe AP courses as loaded with material that they must absolutely cover that AP necessarily does our students much good. That said, students, parents, and schools seem to be invested in AP courses. My school, like some other schools, requires students have an A- average and teacher recommendation to take AP. If students have a lower/close average, they can appeal to take AP, and the English department reads their three common prompt papers (all students in a given grade write on the same topic; for example, our common prompt this trimester was about Updike’s short story “A&P”). So, the concern is that students might actually have a really good portfolio of common prompts, and perhaps their grades will actually be higher because they are turning in better final drafts. Well, essays are not the only form of evaluation I will do, but I admit I am looking at higher grades. I don’t know how many of my students have the desire to take AP Language and Composition next year. I don’t know if I am looking at recommending large numbers of students to AP. I have been upfront about what I’m doing with colleagues, and my administration is supportive (ecstatic, actually). So, I suppose I will just worry about this problem if it arises later this year.

- What about a timed writing situation? Fair enough, English teachers like to assign timed writing. Deadlines are a very real part of every person’s life, but outside of school and standardized tests, I have never had to produce a coherent, organized, well-developed piece of writing in under a half hour. Or a class period. Have you? I do not get the fetish for timed writing, I admit. I’m not sure what we learn about students’ ability to write thoughtfully on a topic in a timed situation. I think it confuses students when we think we emphasize the writing process and then ask them to produce a timed writing, no chance for editing and correction. No wonder they turn in first drafts and don’t edit them. And then we complain about that! Students can’t figure out what we want!

I am sure there are other issues I haven’t considered. Feel free to ask in the comments.