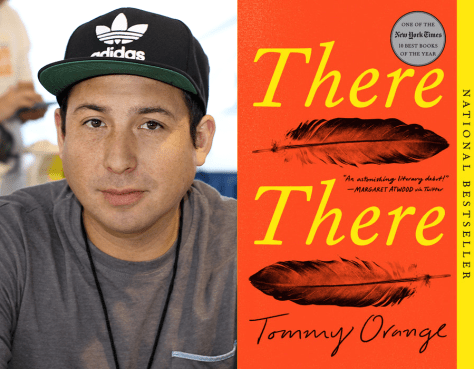

In my last three posts, I have described how my teaching partner James and I approach teaching Tommy Orange’s novel There There. In this final post, I will explain how we wrap up the study of the novel, suggest additional resources to use in teaching Native Voices, and share a summative assessment we use with our students.

James and I decided we wanted students to finish the entire Powwow section before we discussed it since that part of the book moves quickly among the different characters, but at about 60 pages makes up 3 reading assignments. Rather than plunge into discussion of this fast-paced part of the book, we paused to show students this video from Vox about the Native boarding schools, including the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. This video also touches in the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), which will be challenged in the Supreme Court case Brackeen v. Haaland this year. Our students found this video very interesting. It covers a great deal of important ground that is not covered in great detail in the novel. ICWA connects to the character Blue , who is adopted by White parents and must reclaim her Cheyenne culture as an adult. I understand that Tommy Orange’s sequel to There There will explore the Native boarding schools.

We also showed students the following video that asks Native people to reflect on several statements and explain whether they agree or disagree and why. It helps students to understand that indigenous people are not a monolith—their backgrounds and opinions on issues that impact Native people vary. Fair warning: the video includes the F-word and one reference to the N-word, so students should be warned.

Once students finish the Powwow section, we will use a class discussion strategy called “Conversation Stations” or “Converstations” to unpack quotes we identified as important in this section. We use big poster-sized sticky paper with a printout of each quote taped next to the paper. Students will travel in groups, discussing the quotes, and capturing their ideas on the paper. Then they will rotate to the next station and add their thoughts to the ideas already written and connect to their peers’ ideas.

James and I assess our students’ learning at the end of this unit through a writing assignment we call “I Used to Think… Now I Think.” This assignment allows students to discuss what they previously believed to be true about Native people and reflect on their learning. What stereotypes did they believe? How have their perceptions changed? Students might consider the following issues from the novel:

- Addiction

- Trauma

- Identity

- Belonging

- Nation

- Family

- Connectedness

Students can weave discussion of symbols and motifs from the novel as well. Some examples might be the spider and its web or reflection and mirrors. We ask students to write one body paragraph explaining what they used to think and then, in two additional body paragraphs, explain what they have learned in the unit, focusing on two different things (one per paragraph). It’s not a five-paragraph essay in that we don’t expect students to write an introduction and conclusion, though sometimes they do. We encourage first-person voice, which is a natural choices for a personal reflection. An optional challenge for students is to include a third learning takeaway. We use a graphic organizer that looks like the following to help students plan.

| Topic | Delete this text and type your topic, the focus, theme, or thread you plan to discuss. |

| I used to think | Delete this text and discuss the beliefs you previously held about the topic. Discuss 2-3 things you used to think about Native people prior to this unit. |

| Now I think 1 | Delete this text and discuss one aspect of your thread or focus that you have learned more about. Think about what has changed. How have stereotypes been altered or eliminated? How did that happen? Identify two pieces of evidence for your learning in the text of There There or other resources. |

| Now I think 2 | Delete this text and discuss one aspect of your thread or focus that you have learned more about. Think about what has changed. How have stereotypes been altered or eliminated? How did that happen? Identify two pieces of evidence for your learning in the text of There There or other resources. |

We use the rubric below to assess the writing. It’s a variation on a rubric I have used for years, originally developed and published on Greece, NY’s Schools’ ELA resources site (which is, sadly, no longer accessible).

I hope the resources shared will help you in teaching Tommy Orange’s brilliant novel There There. If you have additional ideas, please feel free to share them in the comments.